These days, every marketer wants more data. Indeed, if you can accurately predict customers’ behavior, based on analysis of who they are, what drives them, and what they’ve done in the past, you’ll be just that much more effective in marketing to them. And certainly, the more data you have, the more statistically reliable (assuming it’s decent), as you’ll avoid the inevitable inaccuracies around small sample sizes. But even large data sets should never provide the answer itself. We still have to exercise common-sense judgment –whether it’s a programming a machine to display an ad, or if it’s a human being using that information in his or her decision-making. Here are 4 quick thoughts on the topic and why data isn’t always the answer.

No. 1: Don’t Let Data Make Decisions for You, the Lesson of the 2020 World Series

In Game 6 of the World Series this year, we had what many consider to be an almost perfect example of the over-reliance on data. The Rays manager Kevin Cash, up 1-0 in the sixth inning with No. 1 starter Blake Snell on the mound, decided to pull his pitcher after only 73 pitches. There was nothing wrong with Snell. He had been having a dominant performance to that point – 9 strikeouts, no walks, no runs against him. He had owned the Dodgers’ Mookie Betts, the next hitter up who was 0 for 4 against him, as well as Corey Seager, the batter who followed. But with only one out and a man on first, other data suggested to Cash that it was time to pull his starter. For one, it was the third time through the lineup and data showed that Rays pitchers generally fared worse the third time they saw the opposing team’s hitters. So, Cash did what he had done most of the season. He pulled the starter.

The rest of the story, as they say, is history. With Snell out, replaced by relief pitcher Nick Anderson, Betts ripped a double. Then Anderson threw a wild pitch, allowing the tying run to score. Seager grounded to first, and Betts beat the throw home for the Series-deciding run.

Is it possible that Cash was right to take out Snell anyway and it would’ve ended in the same result? Perhaps. But even Betts himself admitted later he was relieved not to have to face Snell again. And sure, it’s easy to second-guess managers. But the point is, Cash was relying on historical data to make his decision about a completely new situation. And sometimes, that can steer you wrong in critical situations, which aren’t always the same as what happened before. In other words, data can sometimes make us believe that life is a constant, but it never really is. It still requires humans to make continuous judgments.

No. 2: Apply Some Common Sense with Small Data Sets

In marketing, we constantly make poor decisions because of data, perhaps due to the opposite reason – a small sample size we take as gospel. Here’s one we’re familiar with: Let’s say, for example, we’re talking about paid search campaign and a keyword such as “corporate training course,” which is set at a broad match. Well, “training” can be pretty broad term to Google. And it can include lots of training terms – even non-related ones such as “weight training” or “cross training.” And sometimes, rarely and randomly, those terms actually convert. So, what do such companies do when they see a converting keyword? They keep the keyword around – even if it borders on the absurd, sinking more dollars into irrelevant ads. All because of a single conversion. But that conversion likely belied the norm.

Why did it convert in the first place? It might be that the individual happened to be one who actually interested in both weight training and a corporate training course. And unlike the baseball example, where the data showed perhaps a truer pattern, here it was simply statistically too small a sample but it was taken as truth. Was it a data point? Sure. Was it a bad one? Yes! (It’s no different from those of us who have experienced the “focus group of one.” If one key individual doesn’t like something, the decision is made to not to move forward, even though the other data might suggest otherwise.) In every case, common sense and human beings still have to play an active role and make good decisions.

No. 3: Machines May Beat People, But the Result Isn’t Always for the Common Good

These days, we’re also getting to the point of having so much data on customers, it’s getting potentially unnerving both for your customers and for you, as machines (guided by flawed human programmers) are determining a lot of what people see. It’s been well documented, for example, how social media algorithms work. If you express interest in a particular topic, the platform (Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, YouTube) will only keep showing you more of that topic. One look at Facebook alone and you realize pretty soon that it starts to only show content that merely confirms what you already believe, or triggers you somehow so you’ll react. From a marketing standpoint, this is as close as it gets to gold because it alters consumer behavior in the way we, as marketers, might want to see. But from a human standpoint as members of a society, it should give us pause, as providing people only what they want is not always good for them. What is the answer for that? We’d always suggest marketers help audiences avoid the absolutist/extremist solutions that are so readily available to them. But that’s a lot easier said than done.

No. 4: Data in the Wrong Hands Can Be Used to Manipulate People

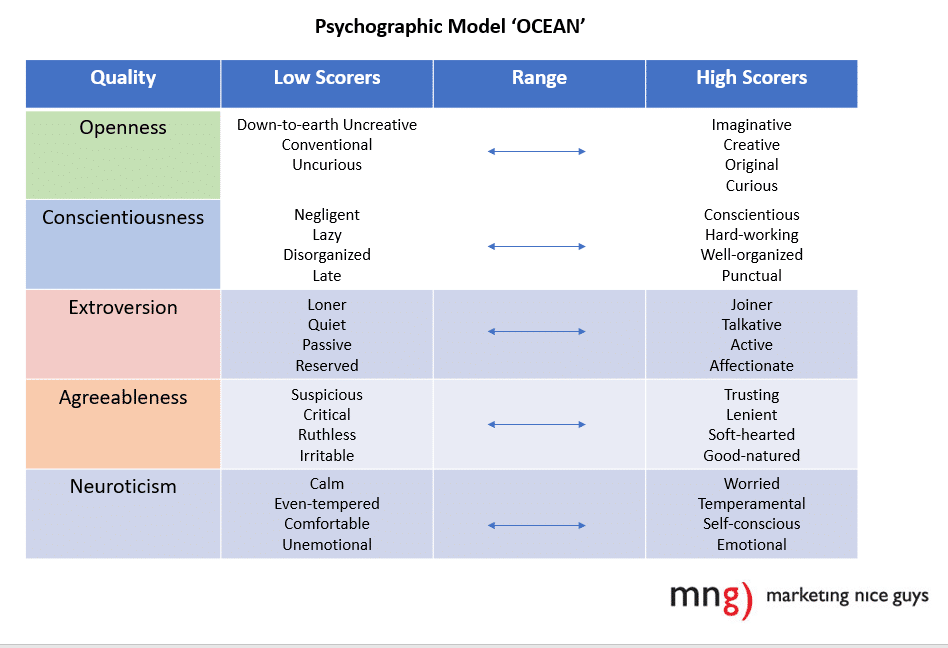

Similarly, consider the case of the now-defunct Cambridge Analytica, which in 2016 was found to have stolen data from Facebook to put together complex psychographic profiles of the social media platform’s users to market on behalf of the Trump administration. While firm was discredited, the psychographic profiles, based on a personality model known as OCEAN, most certainly were not. The model looked at five core areas for determining its personality profile: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Using these five criteria, (above)[1], the firm was able to successfully target audiences who would be susceptible to certain messages, noticeably suppressing the vote for those on the left, while triggering outrage and increased voter turnout on the right.

It’s no secret that psychographic data works. And the more you have accurate data, the more likely you’ll know how a customer will potentially react to your messaging. That’s a huge advantage for marketers assuming they can get their hands on enough of the information. But in the wrong hands, you can also see how it can be used to manipulate unsuspecting customers and audiences.

I think now we find ourselves at a particular crossroads. As professionals in the industry, many of us are rushing headlong into uncovering increasing amounts of data, knowing the benefits of all the information from a pure marketing standpoint. But it’s also too easy now to let machines make decisions for you, and for bad actors to manipulate algorithms and steer customer behavior toward more unsettling ends. I don’t know if any of us have the answer but I would certainly make the call for all parties to be more responsible with the data they do have. I’ve said it before but our goal as marketers should be to help people, not deceive or manipulate them, which I think happens too often these days. Simply put, the fact that we can use a certain data set, doesn’t always mean we should.

[1] Thanks to CB Insights.